Several harmful corporate strategies rely on containing the case at the local or national level where the company often has more power and influence than internationally. Bringing cases to international complaints mechanisms can help change the dynamics and shift the power balance.

People who have suffered human rights abuses as a result of corporate activity often see companies utilising state power to deny them justice, or they may find their concerns diverted in corporate grievance mechanisms that add to the injustice. To conceal their bad practices, companies also abuse voluntary standards and certification systems set up by businesses or multi-stakeholder initiatives, which often have weak compliance mechanisms.

RESOURCE: FIDH guide for victims and NGOs on complaints mechanisms

Taking cases to independent international complaints mechanisms where companies lack direct influence can be an effective way to shift the balance of power. In general, using international complaints mechanisms works best when complaints are part of a wider advocacy strategy to put a spotlight on the company. They can also prove valuable as a way to force disclosure of information that the company has been unwilling to share.

This toolkit only includes international complaints mechanisms with an acceptable level of effectiveness justifying the use of these mechanisms as a counter-strategy.

Approaching United Nations human rights experts (known as special procedures of the Human Rights Council can help put a spotlight on a case. These experts, who cover a range of human rights issues, can take up individual cases by writing to governments and sometimes also to companies. Some special procedures have also adopted “urgent action” mechanisms for time-sensitive cases alleging serious and immediate human rights violations.

These experts can sometimes conduct further investigations by visiting a country where there are reports of serious abuses. Civil society actors often collaborate on cases with UN experts by sending them reports and evidence. You can find a list of the UN special procedures and how to contact them here.

Where civil society actors can make a case that the state or a government body or agency has encouraged, allowed, or contributed to a company’s harmful behaviour, regional human rights bodies may be able to hear complaints.

You can submit a complaint only against a state that has signed the relevant regional human rights treaty, and doing this can raise awareness about corporate human rights abuses that states have failed to adequately address. Possible outcomes of the different regional procedures include the regional body reporting on findings, issuing recommendations, facilitating a settlement, or asking the regional court for a ruling.

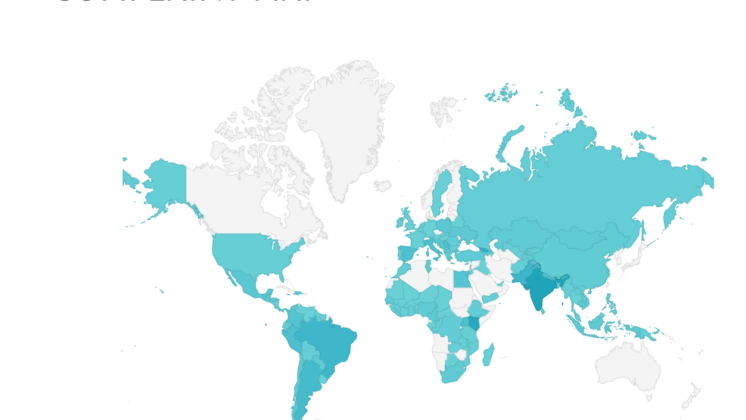

Regional human rights bodies are currently in place for Africa, the Americas, and Europe. Guidelines for submitting complaints are as follows:

– Africa: People or organisations with allegations of violations of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights by a state party to the Charter can submit complaints to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rightsand/or the African Court of Human Rights. The African Charter recognises obligations of businesses towards rightsholders, and the African Commission has several special mechanisms that focus on business and human rights.

– Americas: Individuals and civil society organisations can file petitions to the Inter-American Commission of Human Rightsabout alleged violations of the American Convention on Human Rights by any of the 35 member states of the Organization of American States.

– Europe: There are two legal avenues to raise cases against states in Europe. People alleging breaches by European Union member states of rights protected by the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Freedoms can complain to national equality bodies. People alleging violations of the European Convention on Human Rights by Council of Europe member states can submit complaints to the European Court of Human Rights.

– Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East: Currently none of these regions has a regional human rights body that can receive complaints against states/governments or companies

The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises are recommendations to companies from OECD country governments on responsible business conduct, with a complaints mechanism known as the National Contact Point (NCP) system. Individuals and communities that the behaviour of companies operating in or from OECD countries has harmed increasingly use the NCP system to make complaints.

RESOURCE: OECD Watch guide to the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises

A NCP is a government-supported office in each OECD country that considers complaints against companies that have allegedly failed to meet the Guidelines’ standards. An NCP complaint process generally focuses on resolving alleged breaches through conciliation or mediation, facilitating dialogue between the parties. In their final statement or report to close a complaint process, an NCP can include a determination on whether the company did or did not meet the Guidelines. Some NCPs can request government ministries to attach consequences to companies that do not engage in the NCP process in good faith.

An international coalition of civil society organisations working together as OECD Watch monitor implementation of the OECD Guidelines and support communities and others to file complaints to NCPs. OECD Watch provides detailed guidance on how to file a complaint.

Regional and international development banks generally have an “independent accountability mechanism” (IAM) to enable affected people and civil society actors to bring complaints about companies in which the banks have invested. For example, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, both members of the World Bank Group, have the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO), which can investigate complaints about the negative impacts of projects that involve their financing.

RESOURCE: Accountability Console database of human rights and environmental grievances

The CAO uses the IFC performance standards to assess complaints and is more likely to consider submissions framed in terms of these standards.You can access a list of development banks and other financial institutions and their IAMs here. Civil society guidance on various IAMs’ policies, including their mandate, functions and roles, structure, and complaint processes, is available here. Possible outcomes of complaints to the different IAMs are a compliance review and/or dispute resolution.

While international complaints mechanisms can shift power dynamics, especially as part of a wider advocacy or legal strategy, you should approach these mechanisms with caution. All international mechanisms have limits as to the kind of case they can determine and the remedy and accountability they can result in. Some mechanisms require people bringing complaints to have exhausted all domestic legal avenues before they will hear a case. In most cases, their decisions are not legally binding.

This means that, while companies may have an ethical or moral responsibility to comply with a mechanism’s decisions, or may comply for reputational reasons, there is no legal obligation to comply nor ability to enforce most mechanisms’ decisions. Companies can and do spend considerable time and money on defending themselves against complaints that civil society actors bring to international mechanisms.