Doing business in today’s global economy includes several common business practices through which companies can avoid direct or perceived involvement in activities that result in harmful impacts on human rights.

Global operations and complex value chains

Global value chains tend to be long, complex and non-transparent, not least because of the common practice of outsourcing and subcontracting activities. This has led to huge increases in the efficiency and productivity of global business. At the same time, the global Covid-19 pandemic has shown the limitations and vulnerability of this production model, with severe consequences for business owners and workers alike.[1]

While complex global supply chains have allowed multinational companies to extract value and profit, they also obscure exploitative conditions. This complexity poses difficulties for rights-holders who may attempt to protect themselves from, or seek redress for, human rights abuses and environmental harms. This is primarily because it has become increasingly unclear who can be held responsible or accountable for the violation. The complexity of global value chains has made it easier for companies to avoid liability and responsibility for adverse impacts resulting from their activities.

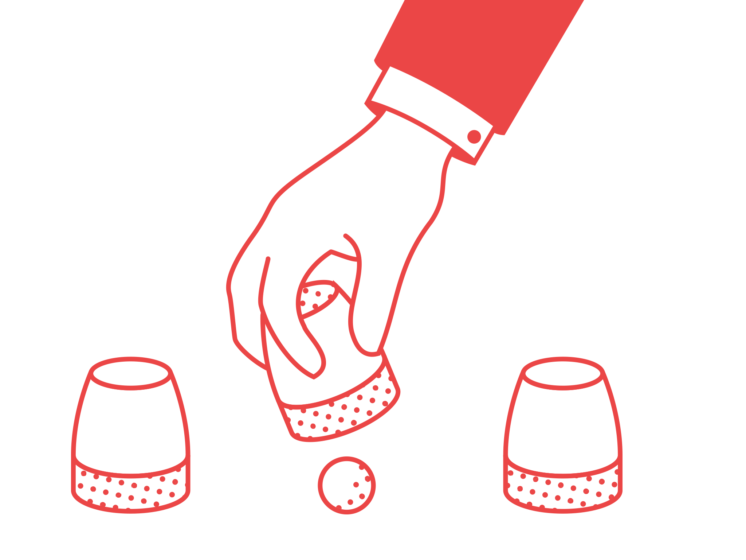

Five ways to construct deniability

Companies use different arguments and strategies to deny responsibility for human rights and environmental impacts within their supply chains. While working with a range of suppliers is a common business practice, when confronted with negative human rights impacts in their supply chains, companies often argue that such impacts are undetectable due to the complexity of the supply chain, or else they place responsibility for those impacts with their supplier.

Companies can also construct deniability by outsourcing high-liability activities and/or recruitment and employment, thereby limiting responsibility for those processes. Another variation of this strategy is when companies opt to disengage from certain business activities thereby cutting their association with human rights harm and thus responsibility for remediation. Companies further construct deniability by directly refusing to disclose information that could tie them to (potential) human rights and environmental impacts.

[1] The editorial board. “Companies Should Shift from ‘Just in Time’ to ‘Just in Case.’” Financial Times, April 22, 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/606d1460-83c6-11ea-b555-37a289098206 (accessed July 6, 2020).; Wilde-Ramsing, Joseph, Marian G. Ingrams, Mariëtte van Huijstee, Ben Vanpeperstraete, and Joris van de Sandt. “Responsible Disengagement in the Time of Corona.” PAX, European Center for Constitutional & Human Rights, Centre for Research on Cultinational Corporation (SOMO), April 2020. https://network.somo.nl/nl/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/04/Time-of-corona.pdf (accessed July 6, 2020).