Transnational companies involved in building the infrastructure in Qatar have been outsourcing the required construction work through long and complex supply chains, which complicates holding anyone accountable for the exploitation of construction workers.

Photo: Jeanne Menjoulet / Flickr

Photo: Jeanne Menjoulet / FlickrA historic construction boom in the Gulf has seen over $200 billion worth of construction contracts being awarded to transnational companies, including from China, South Korea, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Belgium, France, Austria and the UK.[1] A large amount of publicity has focussed on the contracts associated with the building of infrastructure projects in Qatar, directly and indirectly related to the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Revelations of the widespread use of forced migrant labour for the construction of its infrastructure have been made by international trade union confederations, NGOs and media outlets since 2013,[2] in some cases sparking legal proceedings against companies such as the French construction firm, Vinci.[3]

The combination of recruitment and employment practices in Qatar creates the conditions for forced labour and exploitation. Recruitment agencies source migrant workers for the construction operations, typically from India, Nepal and Bangladesh.[4] These recruitment agencies have been implicated in the use of high recruitment fees and debts loans. Once employed in Qatar, migrant workers face restrictions on freedom of movement (e.g. withholding passports), unilateral changing of contracts, unlawful deductions of salary payments and other violations.[5]

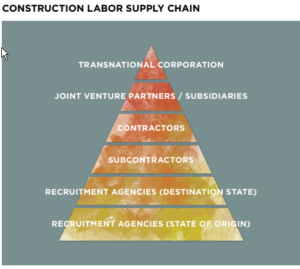

The transnational companies that win the contracts often remain disconnected from the places where workers’ rights are abused, because they operate through complex international supply chains (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Construction Labour Supply Chain. Source: ECCHR, 2018, www.kaimira.de

The chain of migrant labour hiring for construction work in Qatar allows lucrative contract-winning companies from all over the world access to a pool of seemingly endless cheap migrant labour, but with collateral damage: the exploitative conditions and lack of accountability structures for construction workers. The complex chains obscure accountability, making it hard for victims and their representatives to hold individual actors to account.[6]

Most transnational corporations at the top of the chain claim it is nearly impossible for them to oversee the construction worker supply chain. However, the complexity of the supply chain should not be used as an excuse by companies at the top of the chain to look away: since the heightened risks of exploitation that comes with outsourcing of recruitment and employment in Qatar is well-established, and the victims work on large-scale projects undertaken by these same companies, the international normative framework expects them to conduct human rights due diligence to prevent and address human rights abuses beyond their first-tier supplier.[7] Fortunately, some good practices in terms of robust due diligence on recruitment practices have emerged since the exploitative conditions in Qatar received attention, including direct oversight of the recruitment process, the enforcement of no-recruitment fee policies and paying for recruitment fees where they have been charged.[8]

Years of pressure on the Qatari government to address the issue of migrant labour exploitation has recently resulted in some promising reforms. It is too early to assess, however, to what extend this will improve the conditions for migrant workers in Qatar in practice.[9]

[1] Mariam Bhacker, “The Gulf Construction Tracker: Who is employing migrant workers in the Gulf?,” Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/the-gulf-construction-tracker-who-is-employing-migrant-workers-in-the-gulf (accessed October 31, 2019).

[2] The Guardian, “Nepalese migrant worker shares story of labour abuses in Qatar,” Youtube, video recording, November 18, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jls2T3XKlbU (accessed October 31, 2019).

[3] Kim Willsher, “France: Vinci Construction investigated over Qatar forced labour claims,” The Guardian, April 26, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/26/france-vinci-construction-qatar-forced-labour-claims-2022-world-cup (accessed October 31, 2019).

[4] Linde Bryk and Claudia Müller-Hoff, Accountability for forced labor in a globalized economy: Lessons and challenges in litigation, with examples from Qatar (Berlin: European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, 2018), 31., https://www.ecchr.eu/fileadmin/Publikationen/ECCHR_QATAR.pdf (accessed October 31, 2019).

[5] Bryk and Müller-Hoff.

[6] Bryk and Müller-Hoff.

[7] Bryk and Müller-Hoff; Bhacker.

[8] For more information on recruitment policies and practices of construction companies , see: https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/migrant-workers-construction-2018-comparison (accessed June 22, 2020)

[9] ILO, Press release October 16, 2019: Landmark labor reforms signal end of Kafala system in Qatar

https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_724052/lang–en/index.htm (accessed May 14, 2020)