The final week of October saw the sixth round of negotiations for a Binding UN Treaty to regulate the activities of transnational corporations and other business enterprises. As in previous years, SOMO participated. However, this time digitally. A short re-cap.

Photo: UN Photo / Jean Marc Ferré

Photo: UN Photo / Jean Marc FerréNegotiating amidst a pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic materially altered this year’s round of negotiations, impacting the form and degree of state engagement. Due to COVID-19 counter-measures, the negotiations took place in a hybrid format; there were a small number of people representing states, civil society and business physically present at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva while the majority of participants engaged in the process online through live interventions and video messages. Partly due to corona, state participation in this negotiating round was less than in previous years; many representatives were unable to travel to Geneva, online participation from the Americas and Asia was impacted by the time difference, and in-person informal discussions between parties were not possible. Additionally, budget issues at the UN were cited during opening remarks as a major mitigating factor impacting proceedings.

Fault lines and convergence

COVID-19 obstacles aside, there appeared to be insufficient political will across the board to develop the treaty text, with several sessions running short due to little input from most states, even on key articles.

Now that the second revised draft is finally in a solid enough form to allow for negotiations over text, the week exposed the main lines of contention surrounding key concepts, with states like China, Russia and Brazil especially vocal in their objections to the draft’s scope and key definitions, seeking to water down the draft.

State representatives from Africa, Latin America and Asia did reassert their support for the treaty.

Once again, the European Union did not have a negotiating mandate. The EU occasionally commented and asked questions, but gave no input on the text of the draft treaty. This was despite the fact that in response to concerns previously voiced by the EU this draft is more closely aligned with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), and has a broadened scope beyond transnational corporations. The EU’s perceived lack of engagement in the process was met with strong criticism from civil society organisations, including SOMO, culminating in a video appeal from a coalition of European civil society organisations under the hashtag #WhereIsTheEU.

That said, the EU was at least at the table while the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan were some of the most notable absentees. The viability of the treaty and its eventual uptake requires bringing these states to the table.

Representatives of industry and business interests were more engaged this year than in past, which may be a positive sign.

States’ expressions of support for the draft text, and vocal opposition or silence from other states puts into stark relief the question of how such political divides are to be crossed, and how absent or silent states can be brought into the negotiations, and whether enough states will sign and ratifythe eventual treaty.

Despite remaining obstacles, it was encouraging to witness the progress of the draft text.

The text

The second revised draft of the legally binding instrument was published in early August and served as the subject of the negotiations. A leap forward from the previous Zero Draft and Revised Draft (2019), this version is comparably “negotiation-ready”: definitions, structure, legal soundness of provisions and the text coherence have been greatly improved.

One issue that re-emerged throughout the week was that of scope: addressed in art. 3 (1) of the draft text, the instrument would apply to “all business enterprises, including but not limited to transnational corporations and other business enterprises that undertake business activities of a transnational character”. The type of companies this covers raised concerns, with some states and civil society arguing that this broad scope moves beyond the mandate set out in resolution 26/9, and should be restricted to only transnational corporations.

SOMO’s contributions

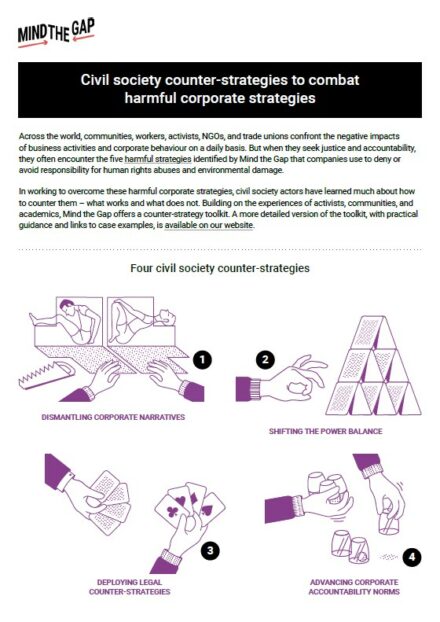

SOMO, together with partners from Mind the Gap consortium and other civil society organisations, participated online and provided text suggestions for the revised draft via oral statements, specifically on the topics of prevention, liability and jurisdiction.

These were the joint contributions:

- Prevention statement presented by ECCJ for Mind the Gap

- Prevention and access to remedy statement presented by FIDH

- Adjudicative jurisdiction statement presented by FIDH

- Adjudicative jurisdiction statement presented by SOMO for Mind the Gap

- Legal liability statement presented by ECCJ for Mind the Gap

Looking ahead

The next steps on this treaty process are laid down in the recommendations of the Chair-Rapporteur and conclusions of the working group, which can be found at the bottom of the draft report of this sixth session.

First, a comprehensive compilation will be made of all the changes to the text that are proposed by states and other relevant stakeholders. Over the coming year, consultations ought to be held at all levels, in particular at national and regional level, for the purpose of exchanging views and inputs on the draft text. By the end of July 2021, the Chair-Rapporteur shall present a third revised draft text, which will form the basis of negotiations later that year.

Work remains to be done to increase state engagement in the process so that negotiations can lead to a strong and widely adopted instrument that will effectively create human rights obligations for business, and remove important obstacles that now stand between rights-holders and access to remedy.